Phagolysosomes... Armed and Dangerous.

Consumption followed by digestion has developed from a nutrition mechanism in unicellular eukaryotes into a highy regulated and indispensable mechanism of host defense against infection in mammals.

Phagocytosis of pathogenic microorganisms by phagocytes, or “eating cells,” is a major host defense mechanism of the innate immune system. The process of phagocytosis was first described at the beginning of the twentieth century by Elie Metchnikoff, who observed ingestion of small particles by cells from starfish larvae.

Phagocytosis is generally defined as;

Phagocytosis and endocytosis are distinguishable by the importance of actin polymerization, which directs membrane motility during phagocytosis, but not endocytosis. Another distinction can be made by the presence of clathrin coats around vacuoles formed during some forms of endocytosis, but not phagocytosis (Greenberg 1986). Recently, one more distinction has been added by showing that endocytosis by IgG Fc receptors (FcγR), but not phagocytosis, requires ubiquitylation (Booth et al. 2002).

When the target particle is too large to be ingested, a process designated “frustrated phagocytosis” may occur, involving activation of pathways partially similar, but not identical, to those activated during phagocytosis.

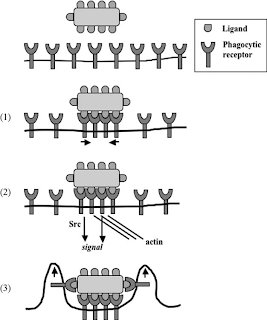

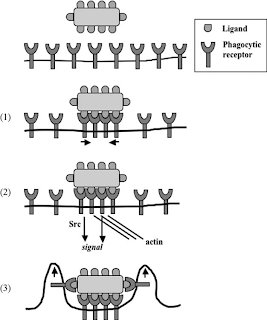

Silverstein and colleagues proposed the “zipper hypothesis” to explain particle engulfment during phagocytosis. According to this hypothesis, phagocytosis occurs through initial attachment of a target via specific phagocyte receptors, followed by complete engulfment, which requires sequential and circumferential (“zipper”- like) interactions between ligands distributed around the particle and receptors on the phagocyte (Griffin et al. 1975, 1976)

This figure illustrates Phagocytosis in three steps. In this schematic model, phagocytosis of a ligand-coated particle by a phagocyte occurs through the following three main steps.

Phagocytosis of pathogenic microorganisms by phagocytes, or “eating cells,” is a major host defense mechanism of the innate immune system. The process of phagocytosis was first described at the beginning of the twentieth century by Elie Metchnikoff, who observed ingestion of small particles by cells from starfish larvae.

Phagocytosis is generally defined as;

The internalization of particles with a diameter of at least 0.5 microns, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, large immune complexes, or apoptotic cells and cell debris.

Ingestion of smaller particles, such a small immune complexes or other macromolecules, occurs through a fundamentally distinct mechanism, called endocytosis.

Phagocytosis and endocytosis are distinguishable by the importance of actin polymerization, which directs membrane motility during phagocytosis, but not endocytosis. Another distinction can be made by the presence of clathrin coats around vacuoles formed during some forms of endocytosis, but not phagocytosis (Greenberg 1986). Recently, one more distinction has been added by showing that endocytosis by IgG Fc receptors (FcγR), but not phagocytosis, requires ubiquitylation (Booth et al. 2002).

When the target particle is too large to be ingested, a process designated “frustrated phagocytosis” may occur, involving activation of pathways partially similar, but not identical, to those activated during phagocytosis.

Silverstein and colleagues proposed the “zipper hypothesis” to explain particle engulfment during phagocytosis. According to this hypothesis, phagocytosis occurs through initial attachment of a target via specific phagocyte receptors, followed by complete engulfment, which requires sequential and circumferential (“zipper”- like) interactions between ligands distributed around the particle and receptors on the phagocyte (Griffin et al. 1975, 1976)

This figure illustrates Phagocytosis in three steps. In this schematic model, phagocytosis of a ligand-coated particle by a phagocyte occurs through the following three main steps.

- Binding. Unligated phagocytic receptors are normally in monomeric state and unable to signal; binding by a multimeric ligand causes receptor clustering.

- Activation. Clustering of receptors facilitates their interaction with signaling molecules such as the tyrosine kinase Syk or members of the Src family, as well as cytoskeletal components including actin. This leads to cell activation and the initiation of membrane motility.

- Entry. Locally increased membrane motility leads to either complete engulfment by newly formed pseudopods (as shown here) or “sinking” of the particle into the cytoplasm. This is followed by membrane fusion and closure of the phagocytic cup.

Comments

Post a Comment